My son has a very, very cheap laptop, and I’ve been surprised how little he uses it. He likes gaming, coding, writing, making videos and podcasts, and all kinds of graphic arts, and this device was a gift for him to expand his skills, to play around in the more powerful and flexible environment of the PC as compared to his locked-down school-issued chromebook.

And yet, he’s taken it out maybe twice in six months– all the while watching video after video about things he wants to someday do on it. What’s stopping him?

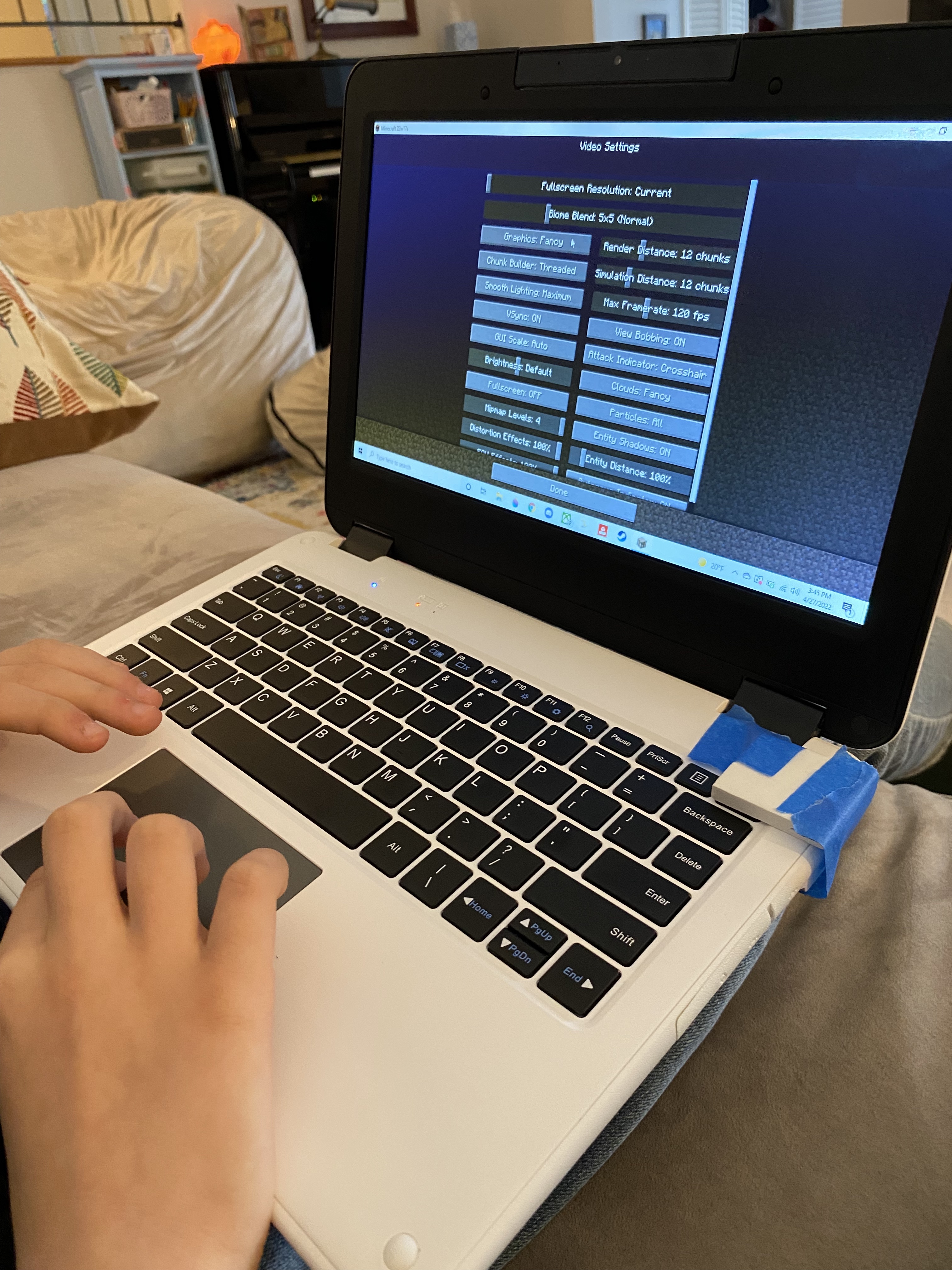

Finally, last time he took it out, I sat next to him on the sofa and watched over his shoulder. Nine year old boys don’t necessarily love their moms doing this, so I had my own computer open as a decoy. I’m sure he was completely fooled! From this vantage point, I saw it. He’d be typing text, maybe into a document or, in this case, a Minecraft command line. Being a human being and a nine year old and my genetic descendant, he’d make a typo every other word or so. And just as I have done three or four times in the last line or two, he’d reach up to the backspace key to go back and change it. All typical. Until, seemingly inexplicably, his whole machine shut down. “Argh! I hate that!” he yelled, then powered it back on and waited. And waited. Then clicked on the program he had been using and waited. And waited. And waited. (I said it was a cheap PC).

About two minuted later, it happened again. Again in another five. Finally I saw what was happening: the Power button was somehow, stupidly, right next to the Backspace button. Apparently this is a thing. And has been for at least 11 years as seen on Reddit, the mothership of internet ranting. WHY?!? People have the actual job of designing computers, and they suck at it.

How perfect a metaphor for writing, though! So often we seem to power off when only a backspace is necessary. Sometimes I’ll be working on a piece of writing and, sometimes after writing many thousands of words, realize I don’t like what I am doing or that I need to change my approach. Reaching for the Backspace button, I realize I don’t yet know how to fix it, and I get so discouraged I can’t make myself work on it at all. Power off! I’ll go hide out in email, or course prep, or more likely eating chips in bed and feeling bad about not writing. It feels safer.

In fact a lot of learning can be like this, too: take for example groups I’ve led or participated in where the aim was to understand and address racism and systemic inequities. As a white educator working among other educators who are predominantly white, so often the work requires unlearning things we thought were true about ourselves and/or the systems in which we work. Backspace! Envisioning change, we find we will have to take apart things that are awfully firmly cemented, like curricula or policies. Backspace! And then racism is so everywhere, and so very baked in to the entire American educational enterprise (big, collective Backspaces) and into our own socialization as human beings and as teachers (backspaces) and the more we look at it the more those backspaces might slip and Power Off. After all, it’s hard to keep mind of one’s own power to effect change in systems that we not only work in but have also been shaped in. It’s…a lot. To say the least.

I fixed my son’s keyboard like this. I am apparently an engineering genius!

I have found that when it comes to writing, this same strategy of adding a barrier works pretty well. The more we can make it impossible to shut down, the better we’ll do. So I do things like make writing dates with friends, switch to freewriting or speech-to-text, use Focusmate, and/or promise writing to people so that it’s just harder to hit Power and quit writing.

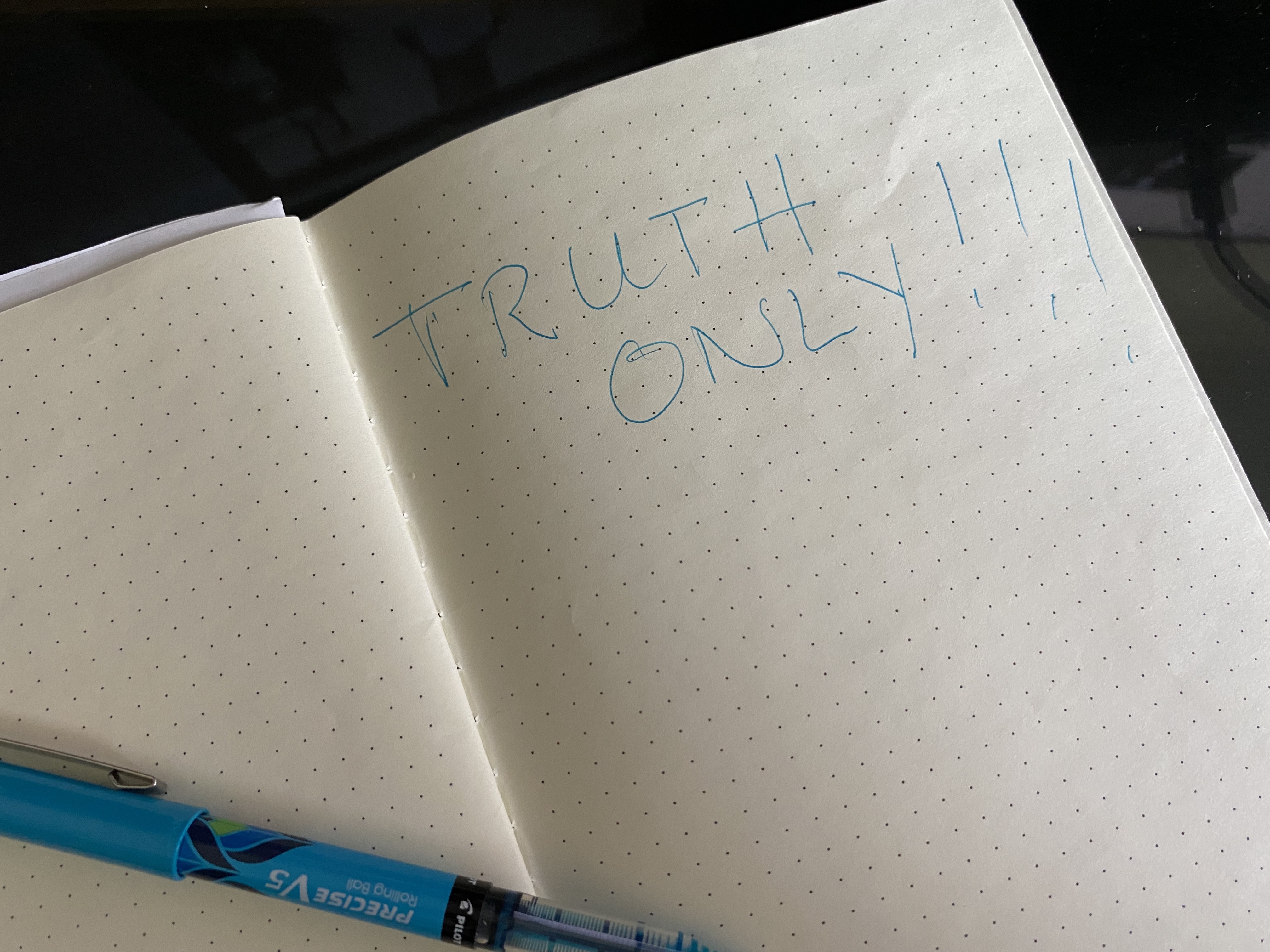

What about the learning communities doing that hard work of subverting racist and other oppressive conditions in education and in the world? The work of making deep change, and of learning deeply, only really gets done when we choose to be there. So while covering the Power button might work on the keyboard, in a learning community part of the work is actually learning how NOT to “Power Off” even when the button is right there. We could quit any time. So many have, and many more have not even begun the work. Yet we keep on showing up, writing our ideas and intentions toward greater freedom and teaching that liberates, Backspacing when we need to while keeping the power On.